THE STUDENT UPRISING OF 1976 was a pivotal moment in the liberation movement against apartheid. For the first time high school students en masse across the country mobilised against Bantu Education and apartheid. The march by thousands of students and subsequent events are reasonably well-known. It is a history that inspired students in the 1980s and, more

recently, in the Fees Must Fall movement.

An important aspect of this history that has been forgotten or ignored since 1994 is the role Soweto students played in forging intergenerational unity, especially with workers. Although Soweto students kept their parents in the dark about the June 16 march, the leadership subsequently recognised the strategic importance of an alliance with workers, in order to mobilise effectively against the system.

Generational politics

When students met on June 13 to plan the march against the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction, they decided not to inform their parents. These young activists believed the older generation was politically conservative and fearful, and they would likely oppose open defiance of the government. A generational fault- line seemed to exist between submissive adults and rebellious youth, whose actions marked a political rupture with their parents. This is an entirely valid interpretation but obscures other processes that tell a different story.

Some parents in 1975 already objected to the state’s plan to impose Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. But their displeasure was limited to written appeals to the authorities to review the policy, which proved ineffective. Once the uprising erupted, a small group of progressive parents met to offer solidarity with the students. They formed the Black Parents’ Association to galvanise broader support for the students and to draw attention to state repression. It was a significant act of solidarity that established a bridge between young and old. The emerging intergenerational unity scaled new heights in August and September.

The student uprising of 1976 was a pivotal moment in the liberation movement against apartheid. For the first time high school students en masse across the country mobilised against Bantu Education and apartheid.

In early August, the Soweto Student Representative Council (SSRC), which had assumed the leadership of the movement, appealed to parents to join them in a march to the notorious John Vorster Square to demand the release of detained students. Approximately twenty thousand residents – parents and students – heeded the call on August 4, but they were violently stopped by the police as they marched along the Soweto Highway. By joining their children on the streets, the main sites of contestation with the apartheid state, parents declared that the struggle triggered by students was also their struggle.

Considering the short notice, the stayaway was a success. However, many workers were also prevented from going to work due to the disruption to local transport, including stoning buses and cars. As a result, an attempt to extend the stayaway by two more days failed. Despite these difficulties, the march proved to be a foundation upon which further united action could be mobilised.

Azikhwelwa

A pamphlet distributed after the strike claimed, “We dealt the racist regime and factory-owners a heavy blow – they lost their profits.” Here students consciously linked the state and bosses and recognised the effect of a workers’ stayaway. Soon afterwards, the SSRC called for a second stayaway on August 23 – 25. This time, students campaigned extensively in the township through door-to-door visits and distribution of leaflets, to persuade rather than coerce workers to join the action. As a result, the first day of Azikhwelwa (stay at home) was a resounding success: a reported 75% of the Johannesburg African workforce were absent on that day. It was also the largest strike in Johannesburg since the early 1960s.

But there was one major constituency that did not heed the call for a stayaway – the hostel dwellers. They tended to be aloof from the townships and were generally uninterested in township politics, least of all being instructed by young people to stay away from work. Moreover, there is little evidence to suggest students had made any serious efforts to explain their campaign

to these workers. Young activists perceived hostel dwellers as strike-breakers and confronted them on their way back from work, which led to a violent altercation during which two students were killed.

An attempt by students to burn down the Meadowlands hostel further inflamed tensions. At this point the sinister hand of the state appeared as the police, supported by the Urban Bantu Council, exploited the anger among sections of the hostel dwellers to organise violent attacks on residents. On the morning of August 24th a crowd of hostel dwellers, armed with an assortment of “traditional weapons”, descended on Orlando West and Meadowlands where they indiscriminately attacked residents, causing several deaths.

This turn of events threatened to ignite a conflagration along ethnic and migrant/ township resident lines and consequently derail the student movement and the generational solidarity of the previous period.

Worker-student unity

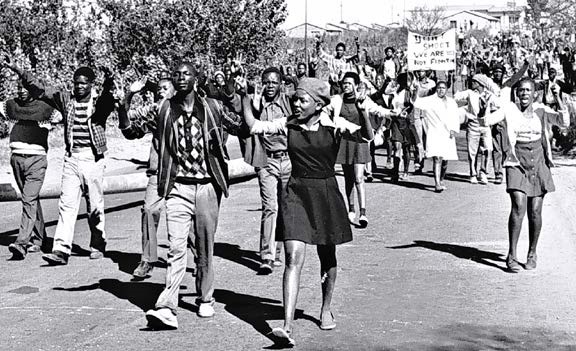

Students and black workers demonstration, Johannesburg, 17 June 1976. Photo: A Diterich. The forging of an alliance between workers and students/youth was a significant strategic achievement of this period.

To counter the destructive consequences of this conflict, the SSRC made serious efforts to win the support of hostel dwellers. A circular distributed on August 27th explained that: The students have nothing against people living in the hostels, they are our parents they are victims of the notorious migrant labour system. They are forced to live hundreds of miles away from their

families, their needs and grievances are ignored by the powers that be. WE are aware that they are packed like sardines in small rooms with no privacy and living under appalling conditions.

Ten days later, another SSRC pamphlet was addressed “To all residents of Soweto, Hostels, Reef & Pretoria”. It countered the state’s effort tomobilise ethnicity to “divide-and-rule” black people. It called for solidarity “to face the common enemy: Apartheid, Exploitation and Oppression”, and declared: “Unity is strength! Solidarity is power!” Confident that they had countered the state’s strategy, the SSRC now mobilised for another stayaway on 13th -15th September. This time campaigning took place in the township and hostels. Another pamphlet appealed for solidarity from workers, specifically hostel dwellers. The shift in tactics yielded positive results and, in sharp contrast to the August events, migrant workers were active in mobilising support for the planned action. As a result, the stayaway was the most successful of the three strikes called by the SSRC. It was the product of learning from political mistakes, and working hard to win sections of the working class behind demands that did not immediately resonate with them.

Despite serious challenges, these stayaways achieved remarkable unity in action between two crucial social and political constituencies, workers and students. Since the early 1970s both had become more organised and radicalised, albeit mostly along parallel lines. Their convergence in 1976 in mass action demonstrated their collective power and capacity to bring the economic heartland of the country to a standstill. It was a lesson that would become a central facet of working class mobilisation over the next period.

The strategic alliance

An important consequence of the student uprising was that hundreds of young people left the country to join the exile movements, and particularly their armed wings. Of even greater significance was the fact that many more students became core activists of the internal mass movements. Connections between students and workers, or communities and workplaces, were strengthened by the entry of the 1976 generation into the world of work, with many joining the emerging independent trade union movement. Indeed, a feature of the period from the late 1970s was the overlapping membership of organisations: youth were unionists, unionists belonged to civic associations and youth organisations, while many others joined political movements, as well as progressive sports and religious formations.

The importance of the strategic alliance between workers and youth/students became even more evident from 1979. In that year, workers belonging to the Food and Canning Workers’ Union went on strike against the company’s (Fattis & Monis) refusal to recognise the union. This industrial action by coloured and African workers won widespread support from communities across the Cape Peninsula, in the form of a consumer boycott. Students led the mobilisation of the boycott, the success of which forced the company to negotiate with the union.

The threat of a similar boycott of Colgate-Palmolive products in 1981 caused a previously intransigent company to accede to workers’ demands. Students also organised two other boycott campaigns – of red meat in 1980 and Wilson Rowntree sweets in 1981 – but these did not achieve victories for workers. Nonetheless, these campaigns demonstrated the consumer power of black communities, mobilised into action largely by students, in support of organised workers.

The forging of an alliance between workers and students/youth was a significant strategic achievement of this period. It did not come easily and encountered several challenges. But workers and students were committed to this crucial dimension of working class unity and power, which was principally responsible for ending apartheid.

Noor Nieftagodien is the Head of the History Workshop at Wits University.

0 Comments